With all the noise, concern and misdirection around what has come to be known as “fake news”, it’s easy to lose of not only the legal history of addressing similar, if not identical, issues. What seems odd today is that those who shout “fake news” often seem cynically tactical and rarely seem as interested in the hard work of establishing the “true” facts as one might reasonably expect.

While “Fake News” may not have been a recognizable phrase the issue is hardly new. History shows that William Randolph Hearst’s papers sensationalized, misrepresented, and sometimes outright fabricated news about the Spanish-American War (1898).

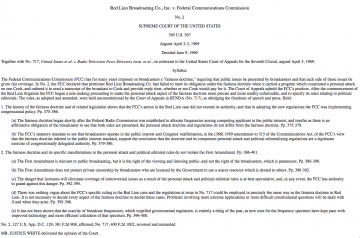

In the U.S. the Federal Communications Commission used the “Fairness Doctrine” in an attempt to maintain honest, equitable, and balanced reporting until 1987 when it was effectively ended by the invocation of free speech principles by the Supreme Court of the United States in Red Lion Broadcasting v. FCC.

Canada’s approach to broadcasting policy is quite different. It does not specifically call out news, but makes certain standards applicable to all programs. It also never explicitly or directly calls for “balance”. Section 3(1) (g) of the Broadcasting Act says “the programming originated by broadcasting undertakings should be of high standard…”. Section 3(1) (i) comes a bit closer to what was the “Fairness Doctrine” when it states “the programming provided by the Canadian broadcasting system should…(iv) provide a reasonable opportunity for the public to be exposed to the expression of differing views on matters of public concern.”

The Television Broadcasting Regulations, 1987 (SOR/87-49), does takes things to a more specific place, perhaps somewhat problematically because it is based on the “should” provisions of the Broadcasting Act noted above, as opposed to clearer jurisdiction conferring provisions. In dealing with “Programming Content” the Regulations provide:

“5 (1) A licensee shall not broadcast

(a) anything in contravention of the law;

(b) any abusive comment or abusive pictorial representation that, when taken in context, tends to or is likely to expose an individual or a group or class of individuals to hatred or contempt on the basis of race, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, sex, sexual orientation, age or mental or physical disability;

(c) any obscene or profane language or pictorial representation; or

(d) any false or misleading news.”

It is also worth remembering Section 181 of the Criminal Code of Canada:

“Spreading false news

181 Every one who wilfully publishes a statement, tale or news that he knows is false and that causes or is likely to cause injury or mischief to a public interest is guilty of an indictable offence and liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding two years.”

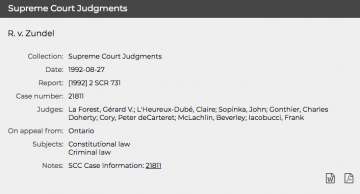

This provision was struck down for vagueness in 1992 by a 4-3 Supreme Court of Canada decision in R.v. Zundel:

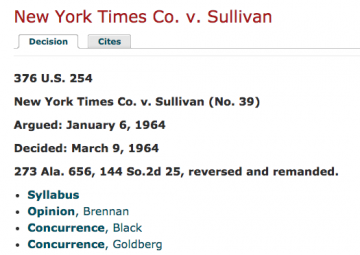

One other interesting note about journalistic truth comes from examining the somewhat different approaches to defamation in Canada and the U.S. Broadly speaking both countries allow a defence to a claim of defamation in limited circumstances even where the the statement made was false. In the U.S. the operative principle comes from the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in New York Times v. Sullivan which established the “actual malice” was required to be shown before press reports about public officials could be considered defamatory.

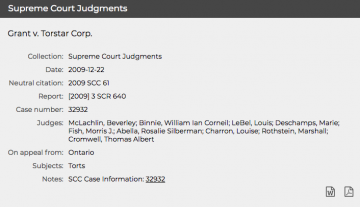

The Canadian approach is arguably more flexible and more sophisticated. Being absent of malice is not enough. Broadly speaking the spirit of the Broadcasting Act concept of “high standards” manifest in more specific form in the Supreme Court of Canada’s adoption of the “Responsible Journalism Defence” in the 2009 decision in Grant v. Torstar. Chief Justice McLachlin summarized the required elements of the defence as follows:“A. The publication is on a matter of public interest and; B. The publisher was diligent in trying to verify the allegation, having regard to: (a) the seriousness of the allegation; (b) the public importance of the matter; (c) the urgency of the matter; (d) the status and reliability of the source; (e) whether the plaintiff’s side of the story was sought and accurately reported; (f) whether the inclusion of the defamatory statement was justifiable; (g) whether the defamatory statement’s public interest lay in the fact that it was made rather than its truth (“reportage”); and (h) any other relevant circumstances.”

Finally we get to fundamental constitutional tests. These do seem to align symmetrically with the differing approaches outlined above. The U.S. 1st Amendment treats freedom of the the press in unqualified terms:

“Congress shall make no law…abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press;…”

The Canadian approach requires a balancing of interests:

-

The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms guarantees the rights and freedoms set out in it subject only to such reasonable limits prescribed by law as can be demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society.

-

Everyone has the following fundamental freedoms:…(b) freedom of thought, belief, opinion and expression, including freedom of the press and other media of communication;

So in Canada free expression can have reasonable limits, perhaps such as requiring a “high standard” of programming under the Broadcasting Act or responsible journalistic inquiry as one possible requirement for a successful defamation defence.

So after all that, here’s the question. Which overall legal approach do you prefer in dealing with “false news”, the American or Canadian one?

Jon